LEGSVILLE.COM

May 18, 2022

©2022 By Burt Kearns

“Bobcat Goldthwait comes out and introduces the clips that Jerry brought, and the clips are running. There’s the famous dance down the stairs from Cinderfella. There’s him doing the incredibly famous boardroom bit from The Errand Boy. And I’m watching Jerry look at himself. He was seventy-six, overweight and nobody knows who he is anymore, and he’s looking at the twenty-six-year-old version of himself when he was super-famous. And I see Jerry look out at the half-full crowd, and then Jerry fell to the ground. And I think he’s dead.”

That scene was from the Palladium in London, September 8, 2002. It was supposed to be the highlight of Steven Alan Green’s career, the pinnacle of twenty-year, transcontinental climb that placed him alongside the ultimate comedy hero of any kid who grew up in the 1960s, especially a Jewish kid born in Long Island and brought up in Beverly Hills. Instead, it was a curse. A traumatic episode that follows Steven Alan Green to this day—and into the next week, onstage in the one-man show he’s presenting at the Yard Theater in Hollywood on Sunday.

“My comedy heroes when I was very young were Groucho Marx, Soupy Sales, and Wallace & Ladmo,” Green says this week. “The latter were a duo in the local Phoenix television market. I went from Beverly Hills to Phoenix back and forth—my father’s second marriage in the Sixties. I saw Groucho when I was a kid, in the street. He raised his eyebrows at me, and it was magical. My first professional show biz gig, I was five years old. A TV commercial for a department store. I played a kid. And then it’s the classic class clown. We moved around a lot, so every classroom that I was brought into in the middle of the day, in the middle of the semester, that was my audience.”

Steven Alan Green with Marc Maron

Professionally, after high school, after performing in musicals and drumming in rock bands, the career kicked off in Los Angeles, around 1981. “I taught myself to play a guitar, strumming a guitar. I had a two-and-a-half octave singing range, and I started doing these coffeehouse gigs. I played the Bla-Bla Cafe where Ricky Lee Jones and Al Jarreau started, and I ran an open mic music venue in Hollywood at a vegetarian restaurant called — get ready for this — The Natural Fudge, which sounds like an Amber Heard daily dish – anyway, having said that, I wish I hadn’t –

“So a couple of comics come into this open mic, and I would play these songs, really heartfelt, almost pukingly sincere songs, and I didn’t think anyone was paying attention. They were talking or they were waiting to go on, or I wasn’t that compelling, and then in between I said, ‘Okay, here’s another song that I wrote just this morning.’ And I played the beginning of ‘Stairway to Heaven.’ And they would laugh. And it was that moment when I went ‘Hmm. This is about getting attention.’ And one of the comedians who was on the show said, ‘Why don’t you go to Comedy Store? You’re very funny. And I’d never heard of The Comedy Store.”

The Comedy Store

Steven Alan Green with Pauly Shore

The Comedy Store on the Sunset Strip was the hot comedy club in the haunted building that once housed Ciro’s nightclub. It was a competitive, cutthroat, coked-up joint where comedians were discovered, Tonight Show spots decided, sitcoms cast, and stars were born. Only a couple of years earlier, Store regulars including David Letterman, Jay Leno and Tom Dreesen led a strike, demanding that the comedians be paid for their work. The owner, Mitzi Shore, who’d won the Store in a divorce settlement from comedian Sammy Shore, fought back, gave in, and still called the shots. “So I cobbled together all the little quick music bits that I did between the songs at the coffeehouse and put them together in a four-and-a-half-minute routine. I signed up for three minutes. I did four-and-a-half minutes and got twenty-seven laughs. And they asked me to come back the next week. And then Mitzi hired me.

“And the next thing I knew, I was unprepared. I was being thrown on shows, including being an emcee, which was easier ’cause you could kibbitz. I had three minutes of material with a fifteen-minute spot, so I would go out and I’d start with gangbusters. I would kill and I was different than everyone else. I had all these different talents, and I had a ventriloquist dummy, and I had a guitar. I did impressions and I told jokes and I messed with the crowd and I would go, ‘I got nothing more.’ See if the light is on (meaning times up), but it ain’t. But I was on shows with everybody to think of: Seinfeld, Bill Maher, Roseanne, Bobcat, Steven Wright…”

Green was semi-standup royalty as a “paid regular” at the Comedy Store for five years – until October 1986, when “Mitzi decided to cull the herd – all the acts that weren’t turning into gold, like a couple of dozen of us. She re-showcased us up in the little Belly Room and most of us got fired. I was demoted from paid regular to non-paid regular.

Steven Alan Green with Robin Williams and Mort Sahl

“It’s one thing to lose your job. It’s worse when they say, ‘You can keep your job, we’re just not gonna pay you.’ So I went up onstage. It was a packed crowd, two hundred and twenty-five people at least, with another twenty-five standing illegally. And I just went up onstage and I said, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, this is my last show. I’m leaving the business. I’m done.’ And you wouldn’t believe how it coalesced the audience. They froze and you couldn’t hear any noise. It was intense. Because every comic was swimming downstream and I was swimming upstream. Like, ‘I’m done.’ I wanted nothing more. The Comedy Store was just filled with backstabbing pricks and snobby agents who made you feel even worse, and Mitzi was becoming less and less reachable. I was fed up. My relationship was with the audience and always has been and everybody else was in the way. So I said, ‘I’m done.’ And as soon as I said that, an enormous black cloud evaporated over my head. And I was funny and I was loose and I didn’t care. And I made everybody laugh.”

It worked so well that Green agreed to come back the following night for another “last performance.” And again. It was good shtick. He got out of town, away from the Store, away from L.A., and worked the road. “I did basically five thousand ‘farewell performances,’ every show my last, sixteen years.” He moved to New York City, into the Chelsea Hotel. He showcased for Letterman and SNL, but the scene wasn’t happening for him. Then his father, with whom Green always had a complicated relationship that was bad for the psyche but good for comedy, suggested: “Go to England.”

“I had played there in ‘82, at the old Comedy Store when I visited my brother, and so I went there on a three-week trip. I went back to the Chelsea, told my girlfriend Kathrine, ‘I’ll be back in three weeks.’

A gun to his head

The London scene was happening. – and welcoming. “I got bookings and I hit the ground running. There were two-hundred comedy nights there and about half a dozen clubs. And they paid money and they got me. No one ever got offended or complained about me, ever, there.”

He got a top agent. “There were basically two Americans who lived there. There was me and Rich Hall. I think we actually got there the same year. Ninety-five. He was and is definitely a better comedian than I am. There’s no question. He’s really funny and you’ve gotta see him. But what I had was something different. I was more of an entertainer. I was more of a provocateur. Most British comics that I was on the circuit with were rather polite and ironic and talking slow, and their jokes were slow burn. And I’m coming on and I’m, ‘Hey! How’s everybody doing? How the fuck are ya!? What’s going on?!’ And I was saying things and doing things on stage that they wished they could. There was the cursing, but they certainly do curse if they have enough alcohol, but it’s standing up on stage and being an America and saying ‘fuck you’ to the system. ‘I quit.’ It’s putting a fake gun to my head. They don’t have guns in England.”

Green scored big in the UK. He did television, he did one-man shows. The audience understood his threat to make every show his last. He’d explain that he’d become addicted to their laughter and the only way to kick the habit was to get out of showbiz. To the Brits, it made sense. They got it. They got him. Well, almost everyone did. The editor of the Sport tabloid took it a bit seriously, with a front-page headline: SEE ME DIE ONSTAGE! “The sicko New York comedian… plans to go out with a bang… His final punchline will be to whip out a gun and blow his brains out before a live audience.”

Steven Alan Green was a hit each year when he and his colleagues made the pilgrimage to the Edinburgh Fringe, the arts festival dominated by comedy. “In England, you do Edinburgh shows. That’s what you do in August. If you’re a star comic, you just go and have fun. People come see you. If you’re a mid-range comic, you’re working out new material for London. And if you’re a beginner, it’s a way to get seen and experience. I went up to Edinburgh with one-man shows. I had great success and it was fun.”

‘High on Laughter’

It was in Edinburgh that Green’s fortunes took a turn. He couldn’t tell at the time. He seemed to be on his way to becoming a comedy Bono or at least a Bob Geldof… or a Jerry Lewis maybe? He did well with his show, Viagra Falls, in 1999. For the August 2000 Fringe, Green produced High on Laughter, a benefit show for Turning Point Scotland, an offshoot of the Turning Point drug and alcohol charity, aka “Princess Diana’s favorite charity.” The lineup at the nine hundred-seat Queens Hall included a mix of British comedians and performers from the States, including Zach Galifianakis, Rick Right, and headliner George Wendt. The show was a success. Green followed up in 2001 by going bigger. The show at the three thousand-seat Edinburgh Playhouse featured British comics including Johnny Vegas and Ian Cognito (who in 2019 actually did die on stage) and Americans Galifianakis, Emo Phillips, and Rick Overton. Green was on a roll. How could he top that?

“The Palladium,” a friend told him. “You’ve got to book the London Palladium.”

“I said, ‘What’s the London Palladium?” What’s the London Palladium? What’s the Palladium? Playing the grand theater in the West End is the equivalent of a vaudevillian making it to the Palace on Broadway. Hope, Bing, Louis, Sinatra, Sammy, Judy, Liza, the Rolling Stones — the Beatles — all made history there. Cass Elliott performed her last show at the Palladium. Green put down a deposit, booking the place for Sunday, September 8, and began rounding up talent, including Galifianakis, Overton, Bobcat Goldthwait, Jim Gaffigan, and Paul Provenza. Max Alexander, the rotund comic who did lots of fat jokes, won a spot in the lineup when he made an offer that Green found difficult to refuse.

“I’m friends with Jerry Lewis,” Alexander said. “Would you like Jerry Lewis on your show?”

Jerry the Hutt

The Jerry Lewis who Steve Alan Green confronted on the yacht looked nothing like the Jerry Lewis he’d grown up with or followed on the Telethon each year. Since the spring of 2001, Lewis had been on a regimen of prednisone for treatment of pulmonary fibrosis. The steroid had caused an incredible weight gain — and caused Lewis’s head to balloon like a basketball, giving him the appearance of a bobblehead or one of those giant-head characters staggering around a street festival in Spain.

“There’s no lunch, brunch, breakfast. He’s just having his assistant bring me popsicles.” Green continues. “And he’s at his computer. He’s writing this book. There’s papers all about the floor and he’s handing me pages and he’s telling me the story about him and Peter Lawford and Marilyn Monroe in the White House bathtub, and he’s telling me all kinds of stories, and namedropping. But the first story he tells me was that, I think it was ’82, he was in Cannes at the premiere of ET: The Extraterrestrial. The film gets a standing O, Spielberg comes out and takes a bow and Spielberg sees Jerry in the royal box and passes off the ovation to Jerry. Jerry stands up and bows like the king that he is.” Green pauses. “Why would a comedy legend tell, a schmuck like – a schmuck like me?” he repeats in perfect Jackie Mason. “Why is he trying to impress me?”

After about twenty minutes of light conversation and more popsicles, Lewis switched gears and laid out his demands: a thirty-six-piece orchestra, travel and accommodations for an entourage of seven and his musical director. “And he’s gonna stay at the Dorchester Hotel and he’s going to bring videos, and there was still no lunch and I’m getting popsicles and I’ve got to use the on-boat bathroom to pish. I opened the medicine cabinet just because I was curious, and it was all hand sanitizers. This was 2002. Very weird.

“And when people would walk through the boat, he was rude to everybody – except his wife, Sam. But even she was walking on eggshells. Jerry was barking orders at everybody: ‘Bring me this! Bring me that—’ There’s no formality, There’s no ‘please.’ Two-and-a-half hours into it, I’m hungry. So I literally excused myself. I said, ‘Okay, Jerry, it was great meeting with you. I’ve got your fax number. I’ll be in touch. Thank you so much.’ And I left. And as I was leaving the yacht, he actually came out, stood on boat and said to me, ‘And by the way, I charge 150,000 dollars worldwide rights if you’re gonna film this, as you said you were.’”

Green drove off, stopped to get a burger, and back in L.A. got on the phone to the UK. He whittled the thirty-six-piece orchestra to eighteen, arranged for a local musical director, Gareth Valentine, who’d conducted Lewis in Damn Yankees, offered him travel and accommodations for four people, and a stay at the Dorchester Hotel. It was all he could afford when raising money for a charity. Then he faxed Lewis the offer.

‘I’m not doing your show!’

“Jerry calls me up. ‘Steven Alan Green? This is Jerry Lewis. And I’m not doing your show.’ Without missing a beat, I said, ‘Good, who the hell needs you?’ And he laughed. And it was at that point that the alchemy of whatever kind of relationship that we had for that summer, was forged. Then it became negotiation. Then it was phone calls from him every day and I was praying it wasn’t him. There were phone calls when he was in a mood, when he was in tears. ‘I’m fat, what’s the press going to say about me? I can’t do this.’ And I’d be, ‘Come on, Jerry, they love you in England. And then the next phone call would be, ‘Look, you’re going to do it this way or it’s not going to happen at all.”

And so it went for weeks. There was the issue of the award. “I told him, ‘We’ll give you the High on Laughter Award for all your incredible accomplishments in philanthropy and comedy.’ And Jerry said, ‘Why don’t we call it the Charlie Chaplin Award?’ And I said, ‘Why’s that, Jerry?’ And he said, ‘Because I was compared to Charlie, and we later became friends, and it would just be great.’ I went to the Chaplin estate. I didn’t want a lawsuit, so I tried to clear it with them, and they said, ‘Absolutely not.’ So it was the Jerry Lewis Award, first recipient, Jerry Lewis.”

Lewis had agreed to do two weeks of press to promote the Palladium show, but the local publicist later said that far less time would be needed. “So I called Jerry. ‘Hi, Jerry, it’s Steven Alan Green.’ ‘Yeah. What do you want?’ ‘So anyway, we don’t need you for the two weeks, just an hour-and-a-half on the phone. That’s all we need. And he said, ‘I’m not doing any press.’ And I paused. I didn’t want to tell him that ticket sales weren’t happening yet. I said, ‘You know, the thing is –’ And he interrupted me and said for the second time, ‘And I’m not doing your show!’ And I was humina-humining like Jackie Gleason. And while I was recovering from that, Jerry fired the final shot. He said, ‘I eat people like you for breakfast!’

“I felt I just seen The King of Comedy and I felt like he was that guy and I had to be De Niro. So I said, ‘You know what, Jerry–’ He didn’t know I was doing a De Niro impression. It was one of those I was doing in my head. I said, ‘You know what, Jerry? I don’t want you on my show.’ Jerry said, ‘What did I say?’ And I hung up on him.”

Showtime

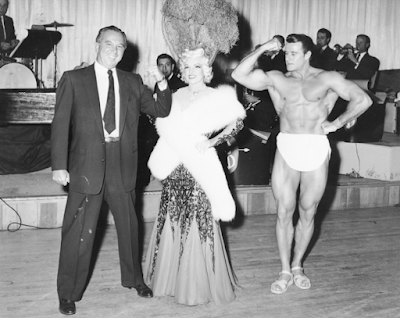

Jerry Lewis backstage at the Palladium with Max Alexander

There were more reversals. Green threatened a lawsuit. On the day Lewis and his entourage were to fly from Los Angeles, they were all in Las Vegas, so new travel arrangements had to be made. Lewis arrived in London with the video compilation of his greatest screen moments and a tall director’s chair with his famed caricature embroidered on the canvas seatback. He’d neglected to bring the sheet music for the orchestra.

At showtime on September 2, the Palladium was half-full — or half-empty, depending on how you want to look at it. By this time, Lewis wasn’t talking to Steven Alan Green. But the show went on.

“The show’s going swimmingly,” Green remembers. “Everyone’s doing great. Zach Galifianakis, Jim Gaffigan.” And then a last-minute addition, Daniel Kitson, took the stage. Kitson was a British comic who’d just won the Perrier Comedy Award at Edinburgh. “And Daniel Kitson’s opening line is, ‘It’s always been a dream of mine to play a third-full Palladium for people who have come to see a dying man.’ Jerry’s in the dressing room. There’s a speaker in the dressing room.”

Then it’s time for the main event. Bobcat Goldthwait has the honor of introducing the video clip montage that will precede the entrance of the great Jerry Lewis. Just as the video package begins to play, the showrunner rushes over to producer Steven Alan Green, who’s watching from the wings. “I don’t know how to tell you this,” he says, “but Jerry is not going to come out of the dressing room to accept the award unless you leave the theater.” Green is apoplectic, but he’s also responsible for the show. He takes a breath. He makes himself scarce.

“I’m hiding in the wings. The clips are running, and the clips are both incredible and cheesy. There’s the famous dance down the stairs from Cinderfella. There’s him doing the incredibly famous boardroom bit from The Errand Boy. I’m on side of the stage, and on the other end, a silhouetted, round penguin figure flanked by his mini-entourage. And I thought to myself, ‘I accomplished this, Steven. I did it. I slayed all the dragons. I kept my powder dry when necessary. I made this happen.’ I was so proud.” He takes a moment to compose himself.

“And I’m watching Jerry look at himself. He was seventy-six, overweight and nobody knows who he is anymore, and he’s looking at the twenty-six-year-old version of himself when he was super-famous. And fifty years ago, almost to the day, he and Dean Martin played the Palladium. I see Jerry look out at the half-full crowd – even though Kitson said one-third– and then Jerry fell to the ground. And the most surreal part of it was the clips were still running. The real Jerry Lewis is now laying on the ground. I think he’s dead.

“And the clips of Jerry going ‘La-dee! Woo!,’ jumping around, are still going and would continue to go for another five or six minutes. The oxygen tank was rushed to his side. His entourage knew just what to do. They stood around him blocking the audience’s vision. I didn’t know what to do. The orchestra’s on stage, the clips end and there’s this long, silent ‘what do we do?’ moment, maybe about thirty seconds, but it was a very long thirty seconds. And then I then rushed out onstage and said, ‘Fooled ya! Okay, just a little technical problem. Just hang on, everything’s going to be cool.’”

Green introduced another comedian. An ambulance arrived. Jerry was carted off, placed in the ambulance, and rushed to… the Dorchester Hotel.

‘I Eat People Like You for Breakfast’

“High on Laughter climaxed with nothing less than high drama,” the review in the London Daily Standard concluded. BBC News reported that Lewis was “resting comfortably” after the collapse “that left him unable to take part in the benefit.” “The story got out there on that new thing called the Internet,” Green says. “It spread around the world, and every comic, every club owner, every agent, manager in London, New York, and LA would continually ask the same unanswerable question: ‘Did Jerry Lewis really collapse?’ Meaning, ‘Did Jerry Lewis fake his collapse? Did the king of pratfalls fake his collapse?’”

Jerry Lewis never called Green to explain. There were no updates. Eventually, Green decided it was a good possibility that Jerry Lewis had faked it. Green talked to attorneys, considered a lawsuit. He dealt with the embarrassment, the trauma of it all. And then someone suggested: Turn it into a show. So he did. He got together with British poet and comedy writer John Dowie and came up with a one-man show called I Eat People Like You for Breakfast! He made comedy out of his personal tragedy.

I Eat People Like You for Breakfast! premiered to much acclaim at the Edinburgh Fringe in 2003. Green went on to perform the show in London and Los Angeles. With Julian Krainin, who won an Oscar as co-producer of Quiz Show, he wrote a screenplay, “a drama,” Green says, “almost Shakespearean, really.”

“Shakespearean” in the way Jerry Lewis plagued Steven Alan Green and began to define his life. But he found he wasn’t alone. “It turns out that there’s a little private club around the world of people who Jerry has fucked over.” Steven Alan Green did his best to move on. He started a charity of his own, The Laughter Foundation (“to help professional stand-up comedians acquire health care and establish a world-class comedy museum”), produced shows, directed films, acted (and starred in the 2013 short, Archie Black, with a cast that included Pete Davidson, Jessica Kirson and Artie Lange), and did voiceover work. For the past ten years or so, he’s spilled out details of his life, fears and setbacks, and offered, gratis, a barrage of one-liners, jokes and concepts, on Facebook. He calls himself a “legend,” ironically, but is among The Comedy Store legends, with his name written on the side of the building, along with the likes of Robin Williams, Richard Pryor, Whoopi Goldberg, Richard Lewis, and George Hirschmann.

A legend returns

Steven Alan Green recently returned to standup, showing up at open mic nights in Hollywood, and performing at clubs like the new Comedy Chateau in North Hollywood. “It was a French restaurant. My opening line my first time there was, ‘Yeah, the Comedy Chateau, great comedy club. Used to be a French restaurant until it was invaded by a German restaurant and rescued by an American restaurant.’ They loved me there, and there’s a couple of others, and I’ve been killing!”

Which leads to Sunday night, May 22, and Steven Alan Green’s return with a one-man show, The Rising Fool. “It’s a light-hearted romp,” he says. “I’m telling all the stories, my best stories. Stories about my parents and my upbringing, and we get through that and we’re now at the Comedy Store. And then we quickly end up in London, and I then I tell the whole story I told you. And then I tell the aftermath of what happened, and I show my seventeen-minute short, multi-award-winning film (Little Things), and I play music, sing a little bit. I will make the crowd laugh continually. I will make fun of myself.”

And finally, twenty years later, he might finally have killed Jerry Lewis. At least the Jerry Lewis in his head. “Yes, I invested a lot of money and time and I put it out publicly that he was the star and I wanted it to work. But also, there was some connectivity where I really felt that I was of value to him. Everyone else was being sycophantic and afraid of him, and I was the only one who stood up and said, ‘No, fuck you. This is what we’re going to do. At the end of the day, I learned two valuable lessons. One, everything that happens, I’m responsible for, because I’m the producer. Even the things that Jerry Lewis did, I’m responsible for, because I hired Jerry Lewis. Two, and I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to apply this in my life, the most valuable lesson I learned: ‘Never work with Jerry Lewis.’

“The whole Jerry Lewis adventure has been both a curse and a, a — an adventure that was very interesting. Jerry was one of the only people I felt who got me. He was the one person I really felt got me. And the one thing that still haunts me is ‘Did he really get me? Or was he working me?’ And I think it was a little bit of both.”

Steven Alan Green stars in The Rising Fool, Sunday May 22 at 7 PM at the Yard Theater, 4319 Melrose Avenue, in East Hollywood. Tickets are $20 at EventBrite.com.

999

Burt Kearns produces nonfiction television and documentary films and writes books, including Tabloid Baby, The Show Won’t Go On (written with Jeff Abraham), Lawrence Tierney: Hollywood’s Real-Life Tough Guy (available for pre-sale on Amazon.com), and the recently-announced Marlon Brando: Hollywood Rebel.